| |

| When a car accelerates so smoothly that the stopwatch must be consulted before you realize that you've been driving a sparkling performer, it's a triumph of contemporary American car design. | |

| |

| When a car accelerates so smoothly that the stopwatch must be consulted before you realize that you've been driving a sparkling performer, it's a triumph of contemporary American car design. | |

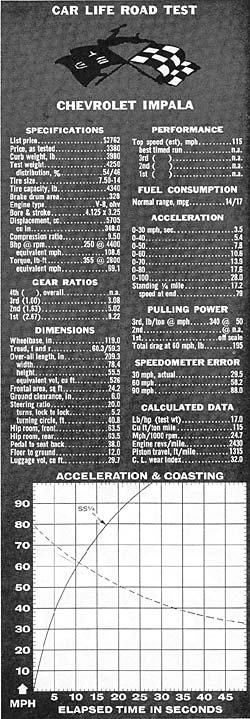

| The 1961 Chevrolet Impala tested for this month's issue is such a car. Equipped with Turboglide transmission in combination with the 348 cubic inch V-8 engine, this four-door hardtop (Chevy terminology: Sport Sedan) was a model of inconspicuous pep. Although rated at only 250 horsepower, the single four-barrel carburetor version of the 348 engine put out well enough to equal the 0-40 mph performance of the 290 bhp Ford Galaxie we tested last month. From that speed on up, the additional power of the Ford resulted in slightly better acceleration; but, in our opinion, not enough better to cause anyone to choose between the two on that basis alone.

Frankly, we were surprised at the performance of our Chevrolet test car. Never enthusiastic over the torque converter types of automatic transmissions, our personal preference has always run toward the type best exemplified by the Hydramatic. Yet, the smoothness of the Turboglide immediately commanded respect. This respect was tempered with regret that it must be bought at the price of performance-but that was before the stopwatch revealed that in addition to its smoothness, Turboglide was no slouch at acceleration, either. |

| The figures in the accompanying data panel tell the performance story, but we'd like to add one footnote: so efficient was the Turboglide at the job of torque multiplication that accelerating the car from a standstill became a problem. Several tries had to be made before a technique avoiding excessive wheelspin was evolved. Obviously, the Positraction limited-slip differential option would be most desirable with this engine-trans combo if optimum stand-start acceleration were the goal.

Fuss-less performance was not the only surprise the '61 Chevy had in store for us-for the first time in many a moon, one of our testers, an inveterate "do-it-yourselfer" who abhors all powerboost accessories, did not complain about the power brakes. In fact, it was not until we reached the stage of our test routine where under-hood component accessibility is checked out that he spied the mechanism concerned and realized that for once he had experienced no problems in adapting from conventional braking. The power steering was, as usual, devoid of road feel, a failing that's apparently the nature of the beast, regardless of make or model. For those who park more than they turnpike, it's a desirable option, but for anyone intending to exploit this car's high-speed cruising ability, it may well be a good one to skip. We can't say too much about the handling qualities of this car, simply because the aforementioned lack of road feel inherent in the power steering prevents one from really knowing how close you actually are to "losing it" in a turn until you have - lost it, that is. Having an aversion to returning test cars to their point of origin in bent-up, burnt-out condition, we make it a practice never to drive them "over our head." With the Chevrolet, you can go fast enough without exceeding this margin. Your own intestinal fortitude (or lack of it) becomes the limiting factor long before the twistiness of the road. For a car designed to haul people, not to win races, that should be enough. |  |

| For those who want more in the way of a "handler's handler" than the Chevrolet offers in its strictly stock form, a switch to the 6-inch-wide rim wheels

that are standard on the 9-passenger station wagons should provide additional resistance to tire roll-under, with attendant benefits in smoother cornering, and audible reduction in tire squeal.

Brakes on the '61 Chevrolet are effective enough in comparison with what competitors are offering |

| to need no further comment, but a feature of the Turboglide transmission designed to make the brakes' job easier certainly does. We're referring to the Grade Retarder, a function of the Turboglide put into effect by simply moving the selector lever to a position on the quadrant marked "G." When this is done, the Turboglide attempts (as much as its fluid coupling will allow) to accelerate the engine speed up to a value corresponding to 2.67 times driveshaft speed. The retarding effect of this move caused us to refer to that position on the selector quadrant as "G for Grab" for the remainder of the test. The Tapley meter recorded a deceleration reading of 300 when "G" was engaged and, although we feel that a greater safety factor (particularly in mountain driving) would be attained with a device giving at least twice this figure, it is definitely a step in the right direction. |